Pandoraviruses were discovered lurking in the mud of Chile and Australia, half a world apart.

In mythology, opening Pandora's Box released evil into the world. But there's no need to panic. This new family of virus lives underwater and doesn't pose a major threat to human health.

"This is not going to cause any kind of widespread and acute illness or epidemic or anything," says Eugene Koonin, an evolutionary biologist at the National Institutes of Health who specializes in viruses.

Instead, the Pandoravirus opens up a host of questions about the origins of life on Earth, according to its discoverer, Jean-Michel Claverie of Aix-Marseille University in France. He says, "We believe that those newPandoraviruses have emerged from a new ancestral cellular type that no longer exists."

The work appears today in the journal Science.

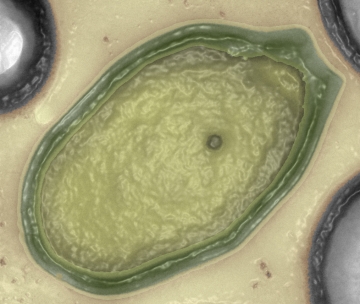

A typical virus is a tiny sack of genetic material that injects itself into a much larger cell and uses it to make more viruses. ThePandoravirus is enormous by comparisonlarge enough to be seen in an ordinary microscope (about 1 micrometer).

It's so big it's hard to even tell it's a virus, Claverie says. "They don't have a regular shape like a regular viruses, they really look like blobs. And so they really look like small bacteria".

Bacteria are single-celled organisms that reproduce on their own. Claverie first stumbled across giant viruses a decade ago, when another researcher brought him one that was misidentified as a bacterium. It was only when Claverie saw it infect amoebas that he realized it was a virus.

After a recent survey found genetic hints of giant viruses in seawater, Claverie and his team decided to go on the hunt. They teamed up with oceanographers and scooped out sediment samples from the coast of Chile and a freshwater pond in Australia.

They brought back the samples and placed them in a solution filled with antibiotics, to kill any bacteria that might have been along for the ride. Then they exposed the samples to their laboratory amoebas.

"If they die, we suspect that there's something in there that killed them," says Chantal Abergel, Claverie's co-author and also his wife.

It worked. The infected amoebas spawned lots of Pandoraviruses. When Abergel and Claverie sequenced the genome of the new virus, they were in for a shock. Its genetic code is roughly twice the size of the record-holding Megavirus. And it seems almost completely unlike anything else on the planet. Only 6 percent of its genes resembled the genes other organisms. Claverie says he thinks the Pandoraviruses may come from a different origin perhaps radically different.

"We believe that those new Pandoraviruses have emerged from a new ancestral cellular type that no longer exists," he says. That life could have even come from another planet, like Mars. "At this point we cannot actually disprove or disregard this type of extreme scenario," he says.

But how did this odd cellular form turn into a virus? Abergel says it may have evolved as a survival strategy as modern cells took over. "On Earth it was winners and it was losers, and the losers could have escaped death by going through parasitism and then infect the winner," she says.

Eugene Koonin, who wasn't involved in the research, isn't buying this theory. "These viruses, unusual as they might be, are still related to other smaller viruses," he says.

The virus's size is probably part of its survival strategy. Amoebas and other simple creatures could mistake it for bacteria and try to eat it, opening them up to infection. "The internal environment of the amoeba cell provides a very good playground for acquiring various kinds of genes from different sources," Koonin says. He thinks that the Pandoravirus's unusual genome may be a mishmash of random genetic material it's sucked up from its hosts.

Nevertheless, Koonin says, the new virus is fascinating. And he predicts this is only the beginning. "We are going to see many, many more giant viruses discovered around the world, some of which, probably will be bigger than Pandoraviruses."

Meanwhile, Claverie is also looking at what Pandoravirus actually does in the wild. The fact that it can be found on different continents, and in both fresh water and salt, suggests it may be a big player in underwater ecosystems around the globe.

Copyright 2013 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/

9(MDAzNTYzNDk2MDEyNDM5NTU1OTc1NDZmZQ001))

0 comments:

Post a Comment